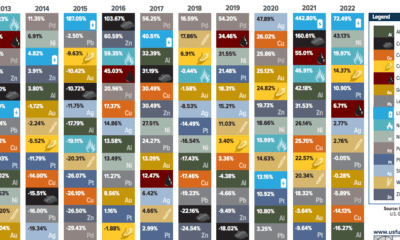

Global markets had their worst ever start in the first trading days of the year, with the S&P 500 eventually shedding 10.5% by early February. Stocks have rebounded since then, but tension is still in the air with record longs on the VIX Volatility Index. Precious Metals For this reason, among many others, investors piled into precious metals in Q1 of 2016. Gold finished up an impressive 15.9%, buoyed by record buying in gold ETFs. Meanwhile, silver and platinum, which are considered precious metals with more industrial uses, were also up in Q1 to a lesser extent: 9.4% and 6.6% respectively. Base Metals Base metals were all over the map in the first few months of the year. Zinc shot up a surprising 20%, though it has been overdue for a bounce back since hitting five-year lows in 2015. Nickel and copper, however, did not perform as admirably. Nickel was in negative territory (-3.1%) and copper ultimately ended up flat, despite a large rally in February and early-March. Energy The energy sector had no real winners, with WTI crude, natural gas, and uranium all ending up in the red. Natural gas was the worst of these with a steep -17.0% drop as it continues to eye multi-decade lows. Some analysts expect more downward pressure on natural gas now that the quantity of gas in storage is 34.2% higher than the five-year average. Food The world’s key agricultural commodities were a mixed bag in terms of performance. Soybeans jumped 4.2% in value, but wheat (1.0%) and corn (-0.3%) only had subtle changes in prices. With many looming questions for Q2, we’re sure that our next quarterly update will be just as eventful. Concerns around a potential Brexit, negative interest rates, stagnating manufacturing, and a potential U.S. rate hike could make for a particularly interesting time period. Chart presented by: First Mining Finance Corp. on Aside from the obvious climate impact they bring, one other downside in particular is spills, which can lead to ecological and economic damage. These can happen due to pipeline leaks, train derailments, or other industrial disasters. This graphic from Preyash Shah provides a visual overview of every oil and gas spill in the contiguous U.S. since 2010. Data is tracked by the U.S. government’s Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA).

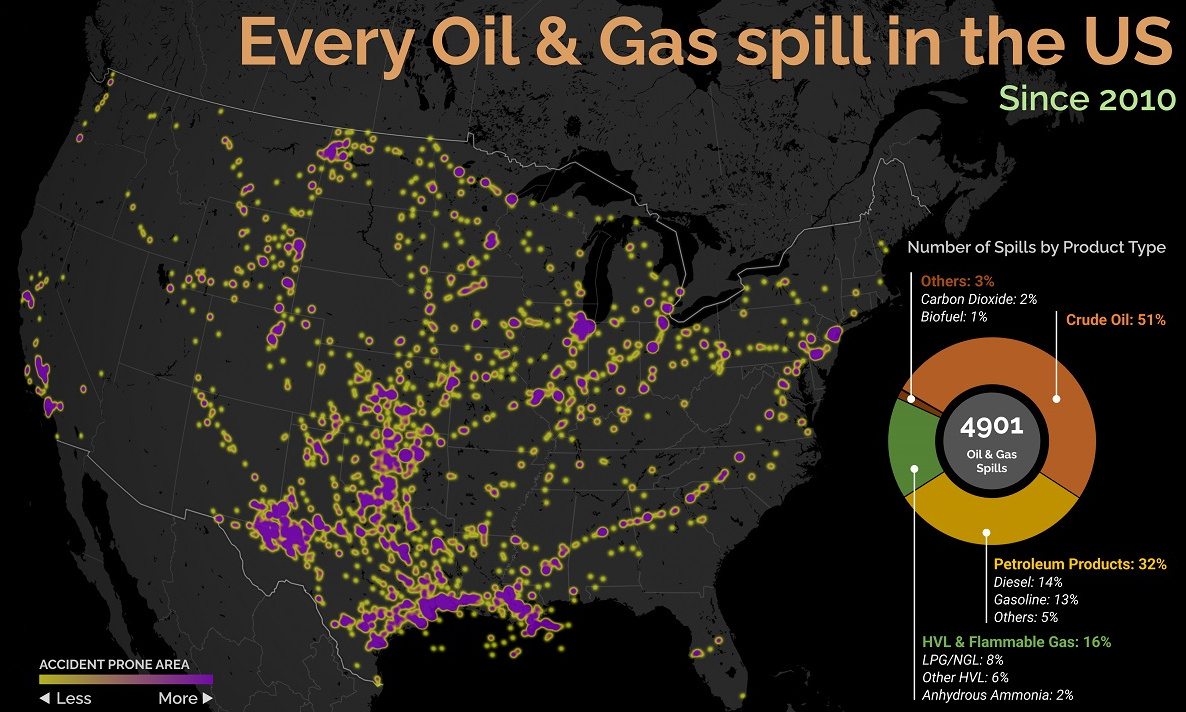

U.S. Oil and Gas Spills (2010‒2022)

The majority of spills that have occurred come mostly from crude oil, followed by petroleum products and gas. Note that this data covers the quantity of spills and not damages or volume.

Crude oil, which makes up just over half of documented spills, is also one of the most costly. Contaminations can persist for years after a spill, and its impact on local mammals and waterfowl is particularly harsh. This has been the case with the Deepwater Horizon spill (also known as the “BP oil spill”), which experts say is still causing harm in the Gulf of Mexico. Other products with lots of spills include petroleum products such as diesel or gasoline, as well as liquefied natural gas or other volatile liquids. Interestingly, liquefied carbon dioxide can also be transported in pipelines, commonly used for carbon capture storage, but requires high pressure to maintain its state. When looking at the location of spills, it’s clear that the South Central states have experienced the highest number of disasters. In contrast, the West Coast has had substantially less activity. However, this makes much more sense when looking at the dominant oil producing states, where Texas and surrounding neighbors reign supreme. Of the 4,901 spills during this period, Texas accounts for 1,936 or roughly 40% of all oil and gas spills. This is followed by Oklahoma, which has had 407 spills and is one of the largest net exporters of oil and gas in the country.

What Causes Spills?

Oil and gas spills actually have a surprisingly long history, with one of the earliest dating back to 1889, when a spill was reported on the coast between Los Angeles and San Diego. Causes have consisted primarily of weather, natural disasters, equipment and technological malfunction, as well as human error. However, they only became a widespread problem around the halfway mark of the 20th century, when petroleum extraction and production really began to take off. This era also saw the emergence of supertankers, which can transport half a million tons of oil but therefore make the risk of spills even costlier. In fact, the biggest spill off U.S. waters after the Deepwater Horizon disaster is the 1989 Exxon Valdez spill in Alaska, when a tanker crashed into a reef and 11 million gallons of oil spilled into the Pacific Ocean.