Among these companies were Airbnb, DoorDash, and Snowflake, all of which raised over $3 billion. To put this into perspective, let’s look at the 10 biggest U.S. tech IPOs of all time.

The Top 10 U.S. Tech IPOs

Airbnb, DoorDash, and Snowflake muscled their way into the top 10, raising a combined $10.3 billion dollars in the second half of 2020. Not adjusted for inflation. More than eight years after going public, Facebook maintains a sizable lead over industry peers. The $16.0 billion IPO by the social networking company is also the second largest in U.S. business history, falling only shy of the $17.9 billion raised by Visa in March 2008.

The Airbnb IPO

Airbnb is an online vacation marketplace that connects vacationers with “hosts” who offer accommodations for short-term booking. Since its creation in 2008, Airbnb has grown in size and influence, disrupting the hotel industry in the process. Airbnb’s IPO raised $3.5 billion by selling 51.5 million Class A shares at $68 each. Airbnb shares closed 112% higher after their first day of trading on December 10, a sign of strong investor optimism.

The Snowflake IPO

Snowflake is a data-warehousing company that provides its customers with cloud-based data storage services. Noteworthy clients of Snowflake include CapitalOne, Logitech, and the University of Notre Dame. Snowflake’s IPO raised $3.4 billion by selling 28 million Class A shares at $120 each. Similar to Airbnb, shares of Snowflake made an impressive climb on their first day of trading, even surpassing the $300 mark. With this achievement, Snowflake became the largest company to double its market cap on opening day.

The DoorDash IPO

DoorDash is a food delivery platform similar in concept to Uber Eats and Grubhub. The business was well-positioned to take advantage of COVID-19 lockdowns which had led to a surge in food delivery orders. DoorDash’s IPO raised $3.4 billion by selling roughly 33 million Class A shares at $102 each. Like its peers, DoorDash rose on its first day of trading, closing at $189.51 a share.

Investor Optimism Outweighs Traditional Thinking

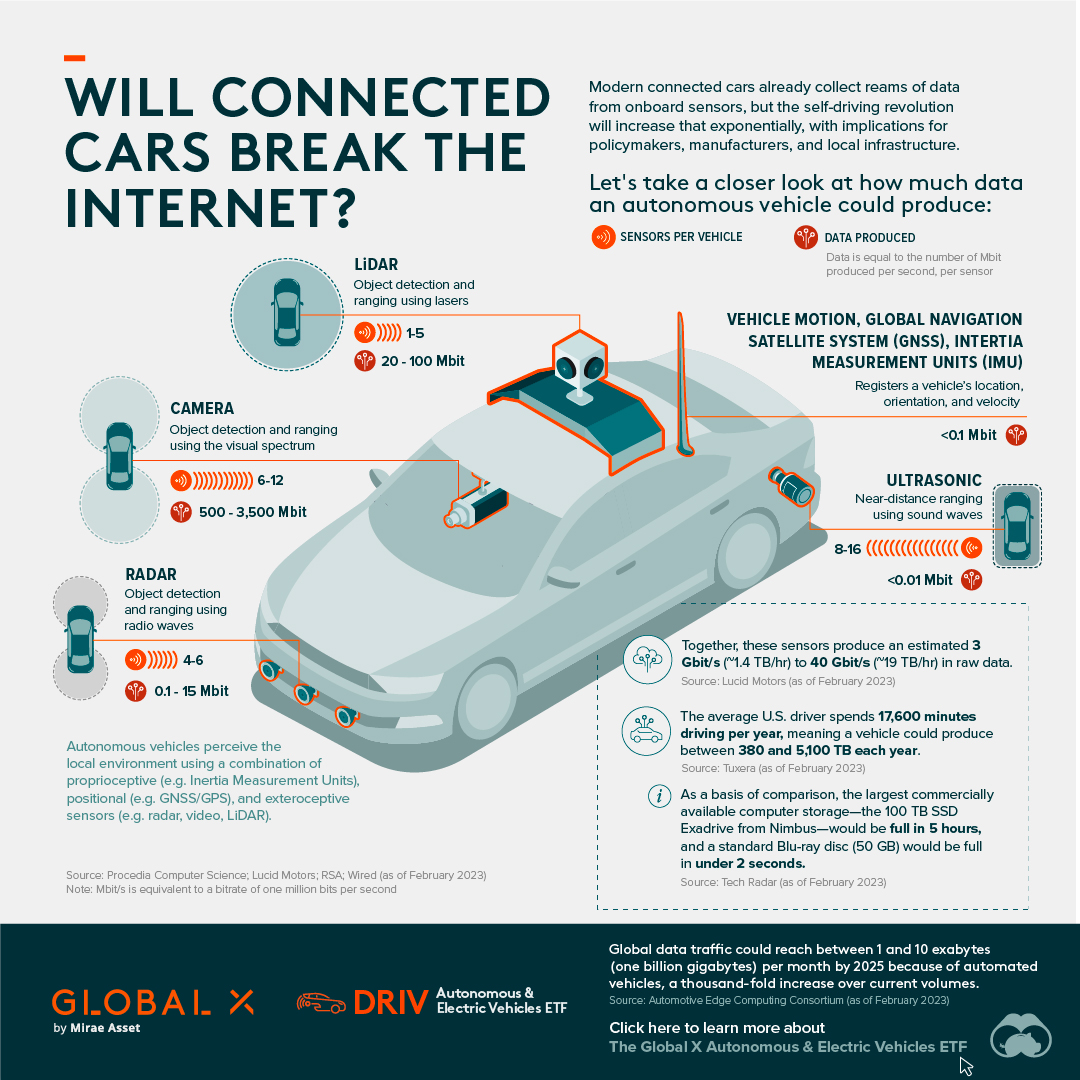

A common factor among each of these tech IPOs is that none of the companies have turned a profit. This has drawn criticism from members of the investment industry, especially regarding DoorDash’s IPO. —David Trainer, CEO, New Constructs Regardless, DoorDash investors remain bullish. As of February 3, 2021, the company’s shares have climbed 27% year to date (YTD). »If you found this article interesting, you might enjoy this post on the world’s largest IPOs. Source: FactSet, Nasdaq Details: Retrieved on Jan. 26, 2020. Not adjusted for inflation. on Today’s connected cars come stocked with as many as 200 onboard sensors, tracking everything from engine temperature to seatbelt status. And all those sensors create reams of data, which will increase exponentially as the autonomous driving revolution gathers pace. With carmakers planning on uploading 50-70% of that data, this has serious implications for policymakers, manufacturers, and local network infrastructure. In this visualization from our sponsor Global X ETFs, we ask the question: will connected cars break the internet?

Data is a Plural Noun

Just how much data could it possibly be? There are lots of estimates out there, from as much as 450 TB per day for robotaxis, to as little as 0.383 TB per hour for a minimally connected car. This visualization adds up the outputs from sensors found in a typical connected car of the future, with at least some self-driving capabilities. The focus is on the kinds of sensors that an automated vehicle might use, because these are the data hogs. Sensors like the one that turns on your check-oil-light probably doesn’t produce that much data. But a 4K camera at 30 frames a second, on the other hand, produces 5.4 TB per hour. All together, you could have somewhere between 1.4 TB and 19 TB per hour. Given that U.S. drivers spend 17,600 minutes driving per year, a vehicle could produce between 380 and 5,100 TB every year. To put that upper range into perspective, the largest commercially available computer storage—the 100 TB SSD Exadrive from Nimbus—would be full in 5 hours. A standard Blu-ray disc (50 GB) would be full in under 2 seconds.

Lag is a Drag

The problem is twofold. In the first place, the internet is better at downloading than uploading. And this makes sense when you think about it. How often are you uploading a video, versus downloading or streaming one? Average global mobile download speeds were 30.78 MB/s in July 2022, against 8.55 MB/s for uploads. Fixed broadband is much higher of course, but no one is suggesting that you connect really, really long network cables to moving vehicles.

Ultimately, there isn’t enough bandwidth to go around. Consider the types of data traffic that a connected car could produce:

Vehicle-to-vehicle (V2V) Vehicle-to-grid (V2G) Vehicles-to-people (V2P) Vehicles-to-infrastructure (V2I) Vehicles-to-everything (V2E)

The network just won’t be able to handle it.

Moreover, lag needs to be relatively non-existent for roads to be safe. If a traffic camera detects that another car has run a red light and is about to t-bone you, that message needs to get to you right now, not in a few seconds.

Full to the Gunwales

The second problem is storage. Just where is all this data supposed to go? In 2021, total global data storage capacity was 8 zettabytes (ZB) and is set to double to 16 ZB by 2025.

One study predicted that connected cars could be producing up to 10 exabytes per month, a thousand-fold increase over current data volumes.

At that rate, 8 ZB will be full in 2.2 years, which seems like a long time until you consider that we still need a place to put the rest of our data too.

At the Bleeding Edge

Fortunately, not all of that data needs to be uploaded. As already noted, automakers are only interested in uploading some of that. Also, privacy legislation in some jurisdictions may not allow highly personal data, like a car’s exact location, to be shared with manufacturers.

Uploading could also move to off-peak hours to even out demand on network infrastructure. Plug in your EV at the end of the day to charge, and upload data in the evening, when network traffic is down. This would be good for maintenance logs, but less useful for the kind of real-time data discussed above.

For that, Edge Computing could hold the answer. The Automotive Edge Computing Consortium has a plan for a next generation network based on distributed computing on localized networks. Storage and computing resources stay closer to the data source—the connected car—to improve response times and reduce bandwidth loads.

Invest in the Future of Road Transport

By 2030, 95% of new vehicles sold will be connected vehicles, up from 50% today, and companies are racing to meet the challenge, creating investing opportunities.

Learn more about the Global X Autonomous & Electric Vehicles ETF (DRIV). It provides exposure to companies involved in the development of autonomous vehicles, EVs, and EV components and materials.

And be sure to read about how experiential technologies like Edge Computing are driving change in road transport in Charting Disruption. This joint report by Global X ETFs and the Wall Street Journal is also available as a downloadable PDF.