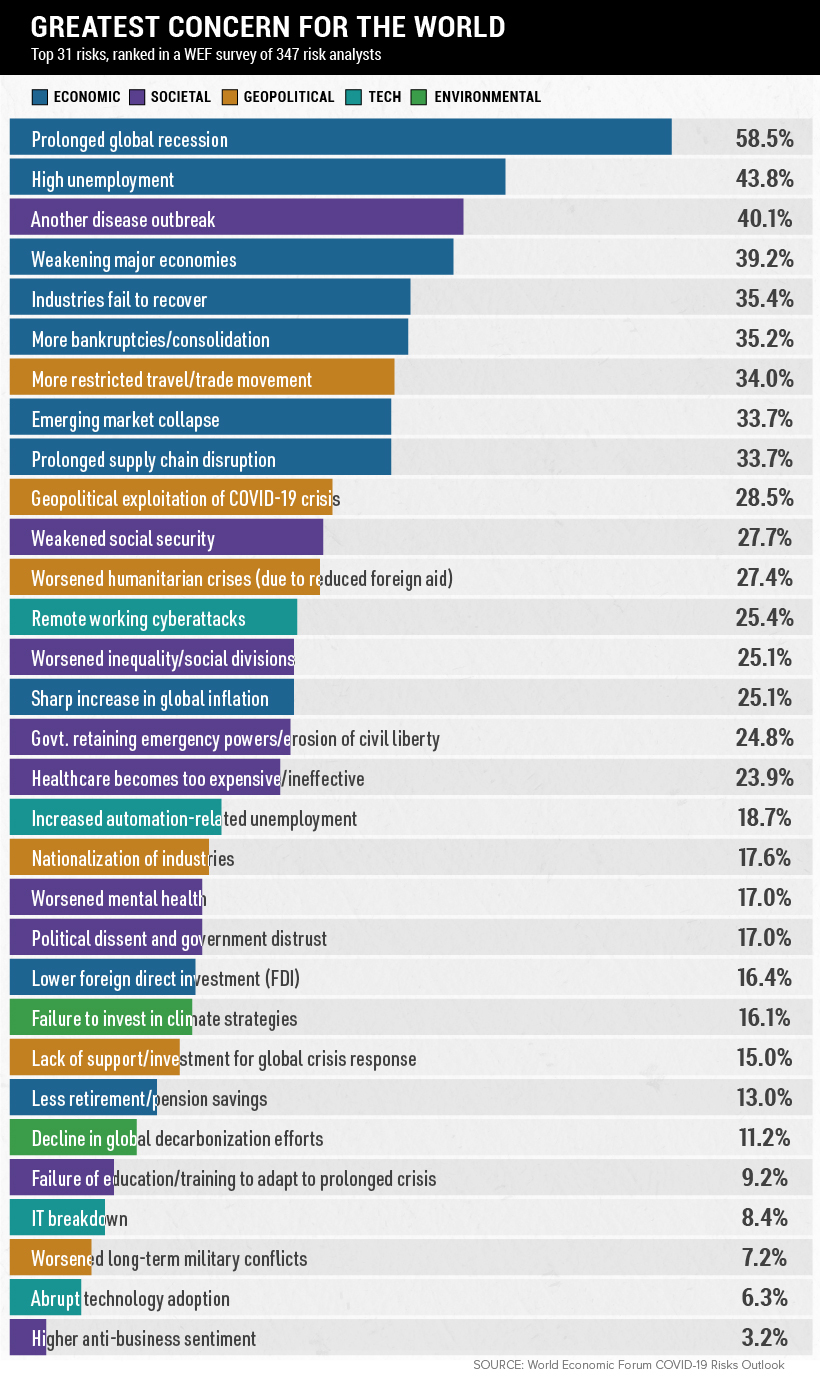

In today’s graphic, we use data from a World Economic Forum survey of 347 risk analysts on how they rank the likelihood of major risks we face in the aftermath of the pandemic. What are the most likely risks for the world over the next year and a half?

The Most Likely Risks

In the report, a “risk” is defined as an uncertain event or condition with the potential for significant negative impacts on various countries and industries. The 31 risks have been grouped into five major categories:

Economic: 10 risks Societal: 9 risks Geopolitical: 6 risks Technological: 4 risks Environmental: 2 risks

Among these, risk analysts rank economic factors high on their list, but the far-reaching impacts of the remaining factors are not to be overlooked either. Let’s dive deeper into each category.

Economic Shifts

The survey reveals that economic fallout poses the most likely threat in the near future, dominating four of the top five risks overall. With job losses felt the world over, a prolonged recession has 68.6% of experts feeling worried. The pandemic has accelerated structural change in the global economic system, but this does not come without consequences. As central banks offer trillions of dollars worth in response packages and policies, this may inadvertently burden countries with even more debt. Another concern is that COVID-19 is now hitting developing economies hard, critically stalling the progress they’ve been making on the world stage. For this reason, 38% of the survey respondents anticipate this may cause these markets to collapse.

Social Anxieties

High on everyone’s mind is also the possibility of another COVID-19 outbreak, despite global efforts to flatten the curve of infections. With many countries moving to reopen, a few more intertwined risks come into play. 21.3% of analysts believe social inequality will be worsened, while 16.4% predict that national social safety nets could be under pressure.

Geopolitical Troubles

Further restrictions on trade and travel movements are an alarm bell for 48.7% of risk analysts—these relationships were already fraught to begin with. In fact, global trade could drop sharply by 13-32% while foreign direct investment (FDI) is projected to decline by an additional 30-40% in 2020. The drop in foreign aid could also put even more stress on existing humanitarian issues, such as food insecurity in conflict-ridden parts of the world.

Technology Overload

Technology has enabled a significant number of people to cope with the impact and spread of COVID-19. An increased dependence on digital tools has enabled wide-scale remote working for business—but for many more without this option, this accelerated adoption has hindered rather than helped. Over a third of the surveyed risk analysts see the emergence of cyberattacks due to remote working as a rising concern. Another near 25% see the threat of rapid automation as a drawback, especially for those in occupations that do not allow for remote work.

Environmental Setbacks

Last but certainly not least, COVID-19 is also potentially halting progress on climate action. While there were initial drops in pollution and emissions due to lockdown, some estimate there could be a severe bounce-back effect on the environment as economies reboot. As a result of the more immediate concerns, sustainability may take a back seat. But with environmental issues considered the biggest global risk this year, these delayed investments and missed climate targets could put the Earth further behind on action.

Which Risks Are of the Greatest Concern?

The risk analysts were also asked which of these risks they considered to be of the greatest concern for the world. The responses to this metric varied, with societal and geopolitical factors taking on more importance.

In particular, concerns around another disease outbreak weighed highly at 40.1%, and tighter cross-border movement came in at 34%. On the bright side, many experts are also looking to this recovery trajectory as an opportunity for a “great reset” of our global systems. ——Gita Gopinath, IMF Chief Economist on Last year, stock and bond returns tumbled after the Federal Reserve hiked interest rates at the fastest speed in 40 years. It was the first time in decades that both asset classes posted negative annual investment returns in tandem. Over four decades, this has happened 2.4% of the time across any 12-month rolling period. To look at how various stock and bond asset allocations have performed over history—and their broader correlations—the above graphic charts their best, worst, and average returns, using data from Vanguard.

How Has Asset Allocation Impacted Returns?

Based on data between 1926 and 2019, the table below looks at the spectrum of market returns of different asset allocations:

We can see that a portfolio made entirely of stocks returned 10.3% on average, the highest across all asset allocations. Of course, this came with wider return variance, hitting an annual low of -43% and a high of 54%.

A traditional 60/40 portfolio—which has lost its luster in recent years as low interest rates have led to lower bond returns—saw an average historical return of 8.8%. As interest rates have climbed in recent years, this may widen its appeal once again as bond returns may rise.

Meanwhile, a 100% bond portfolio averaged 5.3% in annual returns over the period. Bonds typically serve as a hedge against portfolio losses thanks to their typically negative historical correlation to stocks.

A Closer Look at Historical Correlations

To understand how 2022 was an outlier in terms of asset correlations we can look at the graphic below:

The last time stocks and bonds moved together in a negative direction was in 1969. At the time, inflation was accelerating and the Fed was hiking interest rates to cool rising costs. In fact, historically, when inflation surges, stocks and bonds have often moved in similar directions. Underscoring this divergence is real interest rate volatility. When real interest rates are a driving force in the market, as we have seen in the last year, it hurts both stock and bond returns. This is because higher interest rates can reduce the future cash flows of these investments. Adding another layer is the level of risk appetite among investors. When the economic outlook is uncertain and interest rate volatility is high, investors are more likely to take risk off their portfolios and demand higher returns for taking on higher risk. This can push down equity and bond prices. On the other hand, if the economic outlook is positive, investors may be willing to take on more risk, in turn potentially boosting equity prices.

Current Investment Returns in Context

Today, financial markets are seeing sharp swings as the ripple effects of higher interest rates are sinking in. For investors, historical data provides insight on long-term asset allocation trends. Over the last century, cycles of high interest rates have come and gone. Both equity and bond investment returns have been resilient for investors who stay the course.